The small town of Parsons Pond on the west coast of Newfoundland is surrounded by water. The Gulf of St Lawrence is to the west and the nine-mile-long Parsons Pond to the east. The town consists a few small houses, nearly all covered with vinyl siding of various colours. Outside almost every house are skidoos, snow blowers and handmade wooden slays. There is a café, a bar, two old boats locked by ice, trucks, a bridge and the occasional dog. Parsons Pond isn’t big, population three hundred, but inside those small snow covered houses, with smoke streaming into a grey sky, live welcoming and friendly people with personalities so large they make this small place vast.

The small town of Parsons Pond on the west coast of Newfoundland is surrounded by water. The Gulf of St Lawrence is to the west and the nine-mile-long Parsons Pond to the east. The town consists a few small houses, nearly all covered with vinyl siding of various colours. Outside almost every house are skidoos, snow blowers and handmade wooden slays. There is a café, a bar, two old boats locked by ice, trucks, a bridge and the occasional dog. Parsons Pond isn’t big, population three hundred, but inside those small snow covered houses, with smoke streaming into a grey sky, live welcoming and friendly people with personalities so large they make this small place vast.

I like bleak, desolate places. They resonate deep inside me and the people living with this freezing hardship are almost always generous and warm. Parsons Pond residents are no different; if anything, they were the most generous and welcoming people I have ever met, which in a world where walls and division appear to be growing, gives me hope.

Sounding like a bad joke, Bayard Russell, an American, Guy Robertson, a Scot, and myself, an Englishman, travelled from New Hampshire, through Maine, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, to arrive seventeen hours later in Sidney, with only minutes to catch the ferry that would take us to Channel-Port aux Basques, Newfoundland. We had given ourselves plenty of time but a snowstorm in New Hampshire and the shotgun shells randomly scattered around the truck as we crossed the Canadian border slowed our progress.

Sounding like a bad joke, Bayard Russell, an American, Guy Robertson, a Scot, and myself, an Englishman, travelled from New Hampshire, through Maine, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, to arrive seventeen hours later in Sidney, with only minutes to catch the ferry that would take us to Channel-Port aux Basques, Newfoundland. We had given ourselves plenty of time but a snowstorm in New Hampshire and the shotgun shells randomly scattered around the truck as we crossed the Canadian border slowed our progress.

“I’ve booked us on as a small vehicle for the ferry”, Bayard announced as we waited to get our ticket. What?! We were in the mighty GMC, a big silver truck with a black skidoo hanging out of the back: this was no small vehicle. “Look around Nick!” Bayard told me. Large flakes of wind driven snow smattered against a line of tractor and trailers, monster trucks towing skidoos, large vans, and the very occasional car, all with engines running, all with heaters turned to full. I suppose Bayard had a point. As we chatted with the woman at the ticket kiosk she didn’t look twice at our ‘small vehicle’, and we joined the line inching towards the ferry.

Seven hours after boarding, we arrived in Channel-Port aux Basques. The snow and wind had increased. Exhaust fumes streamed into the cold sky, mingling amongst a stippled layer of thick black cloud. Most of the vehicles pulled straight into the Tim Hortons coffee house car park. I Imagined how well a person would do owning a café that sold coffee and not the dishwater masquerading as coffee would do here, but what do I know about business? A man wrapped in several layers of clothes ran past, pumping his legs like a rugby player warming up before a game, but he wasn’t on any kind of fitness campaign, he was just heading for the coffee shop.

Bayard was relaxed behind the wheel of his GMC even after hours of snow covered roads. The Atlantic was always nearby as we drove north. Skeletal trees heavy with snow and large frozen lakes blurred in and out of focus. I was struggling to stay awake, still feeling the effects of the sea sickness tablets I had necked before the crossing. At two in the afternoon we reached Cow Head, the town before Parsons Pond. Bayard had booked a cabin at Shallow Bay Motel: “Can you believe it, they rang me back after my original booking to tell me they give discounted rates to climbers” he said with his slow American gravel, laughing and shaking his head.

The cabin was warm and tidy. It had a fridge, a flat screen TV, a microwave, and the most horrible imitation log burner. We unpacked in driving snow that misted the road, heaving duffel bags that were wedged between the skidoo and the sides of the truck. In no time the tidy little cabin was cold and the floor was covered in snow. Bloody hell it was cold. The walls of the cabin creaked and the window frames, loaded with fresh snow, rattled, but with the thermostats turned to full, and the horrible electric log burner glowing, we were soon comfortable. The tacos Bayard cooked up were warming and delicious, and I had wolfed two down before stopping abruptly: “Oh dude, I’ve done you wrong, there’s lard in the beans”.

So far on the trip I had climbed a few days in New Hampshire, one day with Guy and two days with Kevin Mahoney. Kevin was the ultimate MOG (Man Of Girth). He made climbing thin ice and hard mixed look like an illusion: he hardly ever reversed, it was something to behold a frame so large continue moving up. Kevin and I had climbed four routes over two days: The Roof and Remission Direct Direct, on the first day, then an unnamed route to the right of Black Pudding Gully and Tripesickle on the second. I didn’t feel particularly warmed up or used to the cold. I was going to perish. I’m normally OK with the cold, but December in Spain had lowered my tolerance. How was I ever going to manage to climb?

The following day, one of the locals we met in the café, whom I later found out was called Pierre, pointed at the thin layer of clothes Guy was wearing and said, “You’re going to freeze!” I must admit looking at Guy with his thin frame and lack of layers, I felt better about my chances and somewhat smug. I was wearing so many layers I looked as solid as some of the locals. Yes, he was going to freeze. Pierre laughed a throaty coughing laugh between drags on his fragrant cigarette, before delivering further piss-taking in the Bristolian-Devonian-Cornish-Scottish-Irish-Canadian Newfie accent. His thick walrus moustache was made up of grey and ginger whiskers, some much longer than others, each of which appeared to have a life of its own. His red eyes, set inside a face criss-crossed with crevasses, glittered. I warmed to Pierre even though it was minus fifteen, knowing it wouldn’t be long before I became the centre of his savage piss take.

Guy Robertson, Myself, Brad Thornhill. Also from New England, Ryan Stefiuk, Alden Pellett and Pierre. Credit, Bayard Russell.

Tomorrow we would move to a cabin at the far end of the lake for three days. But today, we would skidoo the nine miles along the frozen surface of the pond to check out the area and the cabin before returning for another night in the motel. The cabin was owned by Lamont Thornhill who had been born and raised in Parsons Pond. He looked to be in his late forties and rode a powerful skidoo that would eat anything in its way; he said it was an impulse buy and way too fast for his nerve and age. I felt a pang of jealousy, the skidoo looked a lot of fun. Something strange was happening to me in this cold climate: I was looking longingly at skidoos. Lamont’s younger brother Brad, who would join us tomorrow, lived close by and, like Lamont, had lived in Parsons Pond all of his life. Later in the trip I asked Brad about growing up in Newfoundland and what prospects there were for younger people. He explained since the demise of the cod fishing industry, the oil industry and then the mining industry, there was little left for the younger generation, and most moved off the island. The unemployment rate in 2016 was over 14%, the highest among the provinces, and it continues to rise. Brad and Lamont both worked in mining, spending months away from their homes and families. It felt a sad situation to me that people so grounded in local tradition are forced to leave their homes and families to sustain their lives, and when they return they’re on a countdown to leaving again.

Helping Lamont was Terry, another Newfie born and raised in Parsons Pond and another Newfie who worked off the island. Terry made other locals look small. He wore a large fur hat with earflaps which looked very warm, and my jealousy spread from machinery to items of clothing. Pierre sped away, returning with a dooby hanging from his lips and clinging a jar full of moose meat that he presented to Guy. “That’ll keep ya warm boy,” he said between chesty hacks and laughs. Lamont seemed more serious and in better physical condition than Pierre (his moustache was trimmed and well-kept), but he also had that Newfie trait of generosity: “Stay in the cabin as long as you want. We’ll get you there and come visit, and get you out.”

Another local turned up on his skidoo. He wore what at one time would have been white matching trousers and jacket with some form of camouflage pattern, but they looked like they had a long history and could tell many a tale of moose hunting and fishing trips. He sported a goatee and a pair of wire framed glasses on his large face, and across his shoulder was a rifle with a camouflaged stock. He was reasonably short, but wide. He cracked a Molson Light even though it was nine in the morning, then lit a cigarette and looked a little threatening. But once I got to know Bevin Goosney, it turned out his heart was as large as the engine in his skidoo, and he pushed that engine as fast and as hard as he could.

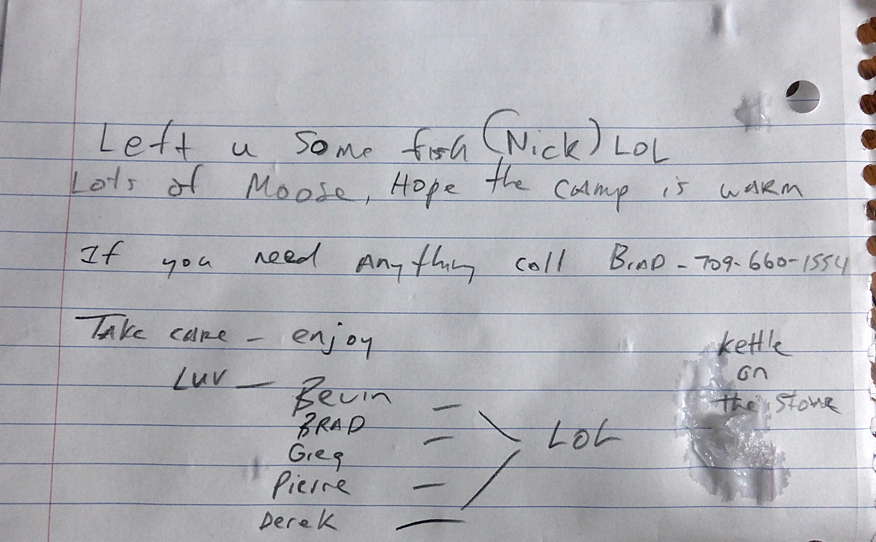

Bevin worked two weeks on, two weeks off in a diamond mine in the Yukon. He would be going away again in three days, but he was here and helping us transport ourselves and gear to the hut. “I’ll get you some moose steaks,” he said before pulling the tab on another beer and lighting another cigarette. I didn’t know how he would take the news I didn’t eat meat, so chose to keep quiet. It had been a long time since I’d felt intimidated by manliness, but watching these guys I felt somewhat inadequate with my soft ways. Eventually I ‘fessed up, but Bevin just shrugged: he didn’t care, each to their own, whatever boy… Psheeeet, another ring was pulled on another tin of Molson Light. I mentioned I ate fish and he said if he could find some he would bring fish steaks when he visited the cabin. At the time I didn’t appreciate the shortage of fish (it must have been a seasonal thing) but later found out Bevin had gone around town visiting friends until he found two halibut steaks, which good to his word he delivered to the cabin.

“Guy has never been on a skidoo before”. Bayard told Bevin. Bevin crushed the empty tin of Molson and threw it onto the snow. Behind his glasses his eyes glittered. Pointing a large finger at Guy he said, “You’re with me!”

The wind came from the west. It blew directly off the dark North Atlantic Ocean. Chunks of ice lapped by syrupy white waves bobbed like fishing floats. The unseen sun provided shadows of sculptured snow that stretched along a frozen surface. A team of six set out on four skidoos across the frozen lake. I was behind Bayard on the Arctic Cat, a seventeen-year-old machine that Bayard had part-bought with two others back in New Hampshire. Guy was sat behind Bevin who was driving so fast he was now just a slightly inebriated speck on the frozen surface of the lake. “I’m not going that fast, this machine belongs to three of us, my history with snowmobiles is not so good” Bayard told me. “Whatdoyoumean, not so good?” I shouted while hanging on to Bayard and being sprayed with snow, terrified that we would hit a lump of ice and flip. “Well dude, the last time I drove a skidoo I set it on fire, burnt it to a cinder… totally destroyed”.

The wind came from the west. It blew directly off the dark North Atlantic Ocean. Chunks of ice lapped by syrupy white waves bobbed like fishing floats. The unseen sun provided shadows of sculptured snow that stretched along a frozen surface. A team of six set out on four skidoos across the frozen lake. I was behind Bayard on the Arctic Cat, a seventeen-year-old machine that Bayard had part-bought with two others back in New Hampshire. Guy was sat behind Bevin who was driving so fast he was now just a slightly inebriated speck on the frozen surface of the lake. “I’m not going that fast, this machine belongs to three of us, my history with snowmobiles is not so good” Bayard told me. “Whatdoyoumean, not so good?” I shouted while hanging on to Bayard and being sprayed with snow, terrified that we would hit a lump of ice and flip. “Well dude, the last time I drove a skidoo I set it on fire, burnt it to a cinder… totally destroyed”.

Most of us stopped for a break at about half way along the lake. Guy and Bevin flew past but Guy was driving now. He reminded me of Dennis Hopper in Easy Rider, although I’m sure Harley Davidsons didn’t travel that fast. Bevin lounged on the back, his gun slung across his stomach, drinking a Molson and smoking. In the distance the mountains were becoming bigger, taking form, they reminded me of the mountains of Norway, Yosemite, the Cairngorms. Grey clouds hung over whale back summits and in contrast, the ice and snow of the lake dazzled with their white. There was clearly a lifetime of climbing in these mysterious hills if only it could be accessed, if only we had the time. Twelve days is what we had, and in the land of notoriously poor weather twelve days was not long. I suppose it was a case of get what we can, when we can, and start thinking about future trips armed with the information gleaned. But coming to Newfoundland is much more than the climbing: coming to Newfoundland is about experiencing the land and the weather and the space and the ocean, and most of all it’s about meeting the people.

Thanks:

It would have been almost impossible to have climbed in Newfoundland without the help and support of the locals who are without doubt, some of the most giving and generous folk I have met. Below is a roll call in no particular order.

Brad, Bevan, BJ, Derek, Pierre, Terry, Lamont – characters all and generous to boot. In the future climbers will be able to stay in Lamont’s daughter’s cabins at Parsons Pond (once they are built in spring), where I’m sure a host of information and skidoo services will be available.

And as always, the hospitality and generosity of my friends in New Hampshire, especially Anne and Bayard.

Rick and Celia at IME in North Conway who always make me welcome, and Doug Madara for just being Doug.

The Arding Slot.

Guy and myself climbing the second ascent of the seven pitch climb, The Arding slot, Western Brook Gulch. The first ascent of this climb was by the Newfoundland activist Joe Terravecchia and Will Carey. Bayard and I met up with Joe and his long term climbing partner Casey, for all things Newfie later in the trip, neither disappointed with the stories they told and their enthusiasm even after twenty years of climbing and exploration in Newfoundland. It was a great inspirational evening. Credit, Bayard Russell.

Got Me Moose Boy.

Guy Robertson approaching Got Me Moose Boy. The first ascent of the climb was by Joe Terravecchia and Will Carey. When Will and Joe first climbed GMMB, the pillar at the base was not touching so the line climbed was by the ice fringes out right until a traverse was made to reach the main body of ice above the first big overhang. We believe this was the second ascent and as the climb was in such great condition we climbed the initial pillar direct.

Fat of the Land. The Cholesterol Wall, Ten Mile Pond.

The way out…

Nice one Nick! Looks wild!!!

Good stuff!

FYI, you’ve got your directions backwards in the first paragraph. Gulf is on the west side, pond on the east… Aside from that, bang on!

Thanks Liam,

I have looked at the map of Newfoundland loads and for some reason I couldn’t get my head around east and west. Some may say I have always had that problem with direction and navigation 🙂

I grew up in Newfoundland, on the west coast. It always confused people when I tried to explain that to them, because of course the island itself is on the east coast.

With all these trip reports lately, I’m definitely due for a trip back home! Great to see the island finally getting the attention it deserves. Incredible spot with great people.