The North Buttress of Nyainqentangla South East first ascent by Paul Ramsden/Nick Bullock. 1600m. ED+

Descent via the East Ridge into the South Valley. October 2nd and back into the valley, 8th.

British West Nyainqentangla Expedition 2016

Supported by:

- Mount Everest Foundation

- Montane Alpine Club Climbing Fund

- British Mountaineering Council

The compilers of this report and the members of the expedition agree that all or any of it may be copied for the purposes of private research.

Contact name and address for further information:

Paul Ramsden

5 Halberton Drive West Bridgford Nottingham

NG2 7GU

Tel. 0780 3082 857

Email: paulramsden100@icloud.com

Acknowledgements

The expedition would like to record its grateful thanks to the following for their invaluable support:

Financial Assistance

- Mount Everest Foundation

- Montane Alpine Club Climbing Fund

- British Mountaineering Council

Equipment

- Rab

- Mountain Equipment

- DMM

- Boreal

Aims of the Expedition

To make the first ascent of the North Face of Nyainqentaglha Feng (7142m) in Tibet

To explore other possibilities on surrounding peaks.

The Team

Paul Ramsden (47) British. Health and Safety Consultant

Extensive rock climbing and mountaineering experience in Europe, Middle East, Africa, North America, South America, Asia and the Antarctic. First winter ascents of Cerro Poincenot and Aig Guillaumet. Winter ascent Fitzroy Supercouloir, New routes on Jebel Misht (Oman), Thunder Mountain (Alaska), Siguniang NW Face (Sichuan), Manamcho (Tibet), Sulamar North Face (Xinjiang), Shiva (India), Kishtwar Kailash (India) , Hagshu NE Face (India), Gave Ding N Face (Nepal) etc.

Nick Bullock (50) British. Writer/Climber.

22 expeditions to the Greater Ranges including India, Pakistan, Peru, Nepal, Alaska. Significant routes: Quitaraju Central Pillar ED2, Fear and Loathing, Jirishanca SE Face, ED3, Chang Himal North Face, Nepal, nominated for the Piolets d’or, Slovak Direct, Denali South Face. Alpine climbing includes six full winter seasons in Chamonix including The Dru Couloir Direct, Colton Macintyre, First free ascent of Omega, First free ascent of the Great West Couloir of the Plan, 1938 route, Eiger, Right Hand Pillar of Frêney.

Introduction

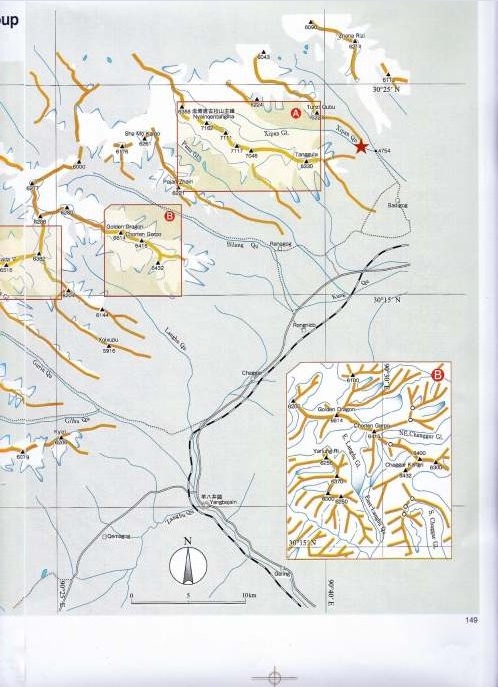

The mountains north of Lhasa are split into the West and East Nyainqentangla ranges. The western range’s highpoint is a cluster of four 7000m peaks also called Nyainqentangla. The highest peak is Nyainqentangla Feng (also known as Nyainqentangla I or Nyainqentangla Main) Nyainqentangla Feng has seen several ascents from the relatively easy south side.

All four 7000m peaks form an impressive north wall several miles long. The glacier beneath the north face appears never to have been visited by climbers and clearly the whole north face presents a spectacular challenge.

Preparation

The Chinese Tibet Mountaineering Association was contacted the year before and contrary to previous experience agreed to our permit almost immediately. It would appear that the West Nyainqentangla is more politically stable than the East Nyainqentangla where I have previously applied for permits.

Our CTMA contact was Emma Xiao. emmaxiao88@outlook.com or 182426592@qq.com

CTMA expeditions are essentially fixed price package deals. The ‘Peak Fee’ included all expenses such as internal travel, accommodation, potters or ponies and the Liaison Officers wages. Unlike other areas however the LO will remain at the road head and it is not normal to have base camp staff. Therefore, you need to be prepared to be fully self-contained from base camp onwards.

Timing

The team arrive in Lhasa on the 9th September and base camp was reached on the 15th. A further 24 days were spent in or above base camp. The intention was

to climb in the stable weather following the rainy season but before things got too cold at high altitude. In retrospect, we probably went several weeks too early.

Travel

We flew from Heathrow with China Southern to Guangzou, where we spent the night and collected our Tibet entry permit. From there we flew the relatively short distance to Tibet, again with China Southern. Flights to Tibet are not cheap and all provide a maximum of 23kg baggage allowance, so additional money was paid for overweight baggage. Extra costs were incurred changing flights to return early.

The CTMA LO and driver met us at the airport and drove us to our hotel in the centre of Lhasa. There was no requirement to visit the CTMA office. We spent two nights in Lhasa (3600m) to acclimatise, then two night on route in Damshung (4200m) also to acclimatise before appending a night in a local’s house at the road head (4700m) between Damshung and Guangbajian. This was actually back in the direction we had come two days earlier. The walk into base camp (5000m) was just one day with ponies.

All travel and accommodation arrangements were made by the LO and were inclusive in the peak fee. The roads are all of good quality and generally a bit dull and the CTMA approved hotels are actually quite extravagant for an expedition.

Road head to Base Camp

The LO organised ponies for the last day of travel into base camp. The only decision we had to make was which valley we should walk up to base camp, which was a harder decision to make than expected due to clouds obscuring the view and poorly detailed maps. The locals assured us we were going up the wrong valley, as the mountain was too steep to climb from that side (sounded promising). Also, they warned us the valley was infested with bears and snow lions (these turned out to be a mythical Tibetan beast that live on glaciers!) which had Nick very concerned.

Base camp was located on flat grass just below the glaciers terminal moraine. A better base camp would be possible about 30 minutes further up the valley but this would require yaks to access. Yaks don’t appear to be used for load carrying in this area and the ponies are only used to grassy rolling hills.

Weather

Despite Tibet being a high-altitude desert we experienced a lot of rain, wind, hail and snow. We believe that the main problem is the proximity of Nam Tso (the second largest lake in Tibet) to the mountain. This high-altitude lake ensures that there is always enough moisture in the air to sustain a generous amount of precipitation.

We intentionally arrived before the end of the monsoon so that we could acclimatise in the poor weather before climbing the route, hopefully in the stable weather of early October but before things started to get much colder at altitude with the start of the winter in late October.

Generally, we experience poor weather, however it wasn’t particularly cold. In retrospect, we should have gone several weeks later. It would appear that the West Nyainqentangla range does not follow normal Himalayan weather patterns.

Diary of the expedition

After establishing base camp an initial recce was mad of the north face to ensure we were camped in the correct valley. The cloudy conditions made this more likely that you might think!

9th – 14th Sept Travel in Tibet

15th – 16th Sept Acclimatisation in base camp and recce of the north face

17th – 23rd Sept Acclimatisation outing on unnamed peaks to the north of

Nyainqentangla.

24th – 26th Sept Rest in base camp

27th – 28th Sept First attempt on route

29th – 30th Sept Wait in base camp

1st – 9th Oct Ascent of North Buttress and descent of East Ridge of

Nyainqentangla South East

10th – 14th Oct Descent from base camp and travel home.

Achievements of the Expedition

Nick Bullock and Paul Ramsden made the first ascent of the North Buttress of Nyainqentangla South East (7046m) over an 8-day round trip from base camp (ED+, 1600m). This was also the third ascent of the mountain and the first British ascent.

Paul Ramsden has written the following article about his and Nick’s ascent:

The strange thing about climbing new routes in China and Tibet is that after a few successful expeditions you suddenly start receiving the Japanese Alpine New. One day it just pops through the letterbox and then keeps coming for the next 15 years! It’s a great record of the peaks of the region and the limited climbing activity that takes place there.

One of the key things is that it acts as a record of the activities of the great Tibet explorer and chronicler Tomatsu Nakamura or Tom to his friends.

While perusing the latest ‘News’ several years ago, I was struck by a set of pictures of the four 7000m Nyainqentangla peaks. As well as referring to the highest peaks in the area the name Nyainqentangla is also applied to the whole mountain chain running west to east, north of Lhasa, in parallel with the Himalaya. I had actually driven past these peaks years earlier in heavy cloud (a characteristic of the area) on my way to the East Nyainqentangla with Mick Fowler to make the first ascent of Manamcho. From the road, the potential of these peaks looked minimal but Tom’s pictures taken from the northeast showed a large north wall falling away from the four 7000m summits, with a particularly striking arête at the northwest end. A plan started to formulate!

Wanting to go to Tibet is very different from actually getting there. First of all, the China Tibet Mountaineering Association (CTMA) is not easy to contact. Email addresses exist but getting a response is a different matter. Once in contact, then the granting of permits is based on the local political situation. If the locals in that area have been kicking off against the authorities, then you will never get a permit. If you do get a permit the situation may change on a week-by-week basis leading to last minute cancellations. With Mick I had been applying for a peak in the East Nyainqentangla for eight years to no avail.

Toms pictures appeared to show a very impressive objective just half a days drive from Lhasa. Being the area most settled by the Chinese it’s also one of the most stable areas. Eventually the CTMA agreed that a permit would be possible, I was amazed!

Nine months later we arrived in Lhasa. Though it wasn’t actually that easy the CTMA announced the week before that they couldn’t email me the Tibet entry pass so we would have to go and collect it in China before proceeding to Tibet. More hassle and expensive flight changes. On the subject of Tibet, let’s just say it’s not cheap!

I have been climbing with Mick Fowler of and on for the last 15 years and consistently for the last 4 expeditions but this years objective was over 7000m, a bit high for a now sexagenarian Mick, so I had to shop around for a new climbing partner.

Now this is not an easy decision as a climbing partner for such routes needs to be the right person. The pool of people however interested in technical climbing on Himalayan peaks is actually not that big for some reason, I can’t understand why, it so much fun!

Anyhow I first met Nick Bullock in Namche Bazaar many years ago. At the time, he seemed like a wild, intense, scary character but when I popped over to visit him in N Wales last year he was writing his second book, while cat sitting, an altogether calmer person. Clearly the last twelve years living out of the back of his van had been good for him. In the end, we got on really well, never a cross word between us, just a steady stream of mild mutual abuse, just the way I like a team to behave.

Tibet had changed a lot since my last visit. Lhasa was about five times bigger with high-rise buildings everywhere. The Tibetan quarter is now totally swamped with new settlers. The road network is totally overloaded with vehicles, though I was pleased to see that many of them are now electric which improves the air quality a lot.

Once you head out of Lhasa all the small towns have grown considerably with extensive Chinese developments everywhere. Its only when you get into the remote villages and farms that things look pretty much as they always have, except the satellite dishes, mobile phone masts etc. Its quite a surprise when a yak herder whips out his iPhone 6 and demonstrates that he has a 3G signal just an hour’s walk from basecamp!

Acclimatisation made what is actually a very short journey to basecamp take a long time. Lhasa is at 3700m so we had two nights there. We then drove for ½ day to Damshung at 4200m, spent two nights there. Spent a night at the road head at 4700m in the headman’s house then walked for just four hours to basecamp with packhorses. So it took six days travel in and at the end of the expedition six hours travel out to Lhasa!

As we arrived at the mountains in bad weather there was much confusion over which valley we should actually go into. The maps of the area were quite poor and location names very confused. In the end, it was worked out but the local warned us that we were approaching the mountain from the wrong side, as it was too steep from that valley, sounded brilliant.

Also, they warned us that the area was infested with bears that would “bite you in the face”. Nicks face was a real picture (look up Nick Bullock and bears on the internet).

At basecamp, we had no staff such as the usual cook and tea boy (couldn’t afford them in Tibet) so it was just us two for a month, pretty intense with someone you don’t know that well.

Basecamp was in a pretty location and once settled in with our psychedelic cooking shelter we felt right at home and ready to explore. At this stage, we still didn’t know if we were in the right valley or not, so there was still a bit of tension in the air.

On the first day Nick decided to take it easy (bed his natural habitat) while I wondered up the valley. Expectations were low due to heavy cloud but then a few hours up the valley it cleared and there it was, big and steep!

Despite the poor weather, we decided to press on with some acclimatisation as you might as well sit around with a headache feeling sick as not when the weather is crap. Acclimatisation involved walking up the glacial moraine below the north face of Nyainqentangla before heading up a 6000m peak just opposite.

Our original plan had been to climb the north buttress of Nyainqentangla’s main summit, which looked just brilliant in Tom’s pictures. However, as we walked below the face we realised there was a hidden monster. The lowest 7000m peak and first on the ridge, Nyainqentagla South East had a recessed north face not really visible from anywhere other than directly below. As we edged into position the clouds cleared to reveal a huge north buttress that was just incredible. It was the sort of route you always dreamed about finding and here it was, we were speechless.

The buttress itself was very steep in the lower half before giving a bit and forming an impressive arête in the upper section. The headwall of the lower face in particular looked problematic. Steep rock with what appeared to be a thin veneer of ice, looked like it might go but only just. If that veneer of ice turned out to be just a bit of powder snow from the last storm, then we would have big problems. Hardly able to contain our excitement we headed back down to basecamp for a rest and to get ourselves prepared for the main event.

I really like the time at basecamp between acclimatising and going for the route, it’s a lot of fun and really relaxed for some reason. Eating food, reading books, tinkering with gear, washing!

Our first attempt on the route is best forgotten about. We camped under the face, it dumped snow, the tent nearly blew away and we retreated. Let’s just call it a gear carry to Advanced Base Camp!

We needed to let the mountain slough some snow for a few days so headed to basecamp and waited. Reading, bread making, eating enormous meals, boredom, debates on whether to take a toothbrush or not, all the usual stuff done in basecamp. Eventually conditions were deemed to be suitable, or as good as it was going to get so we set off for our second attempt.

Luckily the only two really nice days of the trip coincide with our walk back up and our first day on the face. It didn’t last though!

Camped once again under the face things were looking good, perfect weather and a lot less snow on the face than before. We decided that the direct start looked a bit thin in the first rock-band; there is nothing more dispiriting than failing on the first pitch! A gully to the left offered more ice and would allow us to traverse into the centre of the face a bit higher up and avoid the regular spindrift sloughs coming down the centre of the face as an added bonus.

I always enjoy the walk into the foot of the face, as the perspective changes the face rears up alarmingly but as the upper face disappears and the lower pitches are visible in more detail, suddenly the whole thing looks more manageable. I suppose its burying your head in the sand but I always think it’s best to think about such a big route just one pitch at a time. Deal with what’s in front of you and worry about the rest later. If you think about the route as a whole it’s just too easy to get intimidated.

Amazingly the foot of the face was the first time that myself and Nick had ever tied on a rope together!

Once on the face we soon discovered that we weren’t going to get any neve on this trip. The snow was deep, really deep and the only ice existed when things steepened up and the powder had sloughed off. That first day working our way up the lower slopes was really hard work, almost never ending post holing as we worked our way towards the planned first bivy ledge below the ever steepening rock bands above.

I was convinced that the snow arête we were aiming for would give us an excellent camp spot but it turned out to be knife edge sharp with rocks just below the surface and eventually only produced two semi reclining sitting ledges, grim! With us on separate ledges there was no way to put up the tent so I just rapped myself in the fabric, pulled on the duvet jacket and settled down to try and melt some water with the wind constantly blowing the stove out. Open bivouacs in mediocre weather are best avoided, a bad night on your first night on the mountain is a really recipe for a retreat.

As the sun came up we could see that the good weather had gone and we were back to the usual Nyainqentangla cloud and precipitation but the night had not been that back, breakfast was consumed and we were ready to get stuck into the technical ground above.

From our bivy ledge, things steeped up alarmingly. From below we thought this would be the crux of the route. A very steep rock band crossed the full width of the face, in most places it was too steep for ice but in the centre, there was a thin veneer of white covering the rock. Whether this was powder snow or ice remained to be seen but today we would find out if the line would go or not.

We traversed diagonally up and rightwards aiming for some steep runnels and the elusive ice. Much of what had looked like ice from below turned out to be powder snow stuck to the underside of overhangs and a thin de-laminated snow crust on the vertical rock itself. Luckily a series of shallow runnels did hold some goodish ice. Often not think enough to take a full ice screw but if you dug around on the adjacent rock bits of rock gear were available.

Slowly we worked out way up some very absorbing pitches, occasionally hauling sacks. The climbing was excellent; Nick thought it reminded him of the upper part of the Colton – McIntyre on the Grandes Jorasses. Eventually the groove line ended and Nick was forced to climb a steep rock wall, fortunately beneath the snow veneer were a series of flakes that allowed for good if scary hooking, a fine lead.

Then we were though the rock band and looking for somewhere to camp. Determined to have better night’s sleep I announced it was time to test out my latest version of the ‘snow hammock’. Originally a Russian invention, they used the fabric base of a portaledge to trap snow and build an artificial ledge, I have experimented and produced lightweight versions. Version 1 was used last year on Gave Ding with Mick and proved to be effective but just not robust enough, as we found when it froze to the face and ripped when pulled off. Version 2 is a totally different beast! High tech un-ripable fabrics and Kevlar webbing make it both strong and lightweight. Basically, it’s a large rectangle of fabric that you attach to the face with ice screws, fill with snow and then pitch the tent on top. It worked brilliantly and we ended up with a nearly flat camp spot in a truly ridiculous position.

It had been a tough day and we woke pretty exhausted. From this point, we had two options, either follow the crest of the buttress or the more mixed ground on the right, however concerns about the avalanche potential on some of the snow fields and the feasibility of some of the rock bands meant that the crest of the buttress was clearly the best option.

Traversing leftwards we hit the crest and climbed an arête in a pretty wild position. The previous two days however had tired us both more than we realised so we decided to make day three a short one and we stopped as soon as we could find another good spot for the snow hammock. The ledge was even better this time and the tent fitted on comfortably. In the evening, we had great views of the adjacent Nam Tso Lake and could quite literally see the moisture being sucked of the surface ready to dump on us. The lake was so big the route felt a bit like a sea cliff!

Now we were following the crest of the buttress the setting was dramatic but as the route became less technical the snow just got deeper and deeper, which combined with the altitude made for some lung busting pitches.

The fourth camp was good but that night it started to dump snow and at 6700m you suddenly start to realise what a serious position you are in. Retreat down the line would be difficult due too a lack of ice making abolokov threads time consuming to find and we didn’t have enough rack to abseil on rock anchors all the way. Upwards to the summit and hopefully down an easier ridge was the best option but all this snow could make that option hazardous for avalanches.

Dawn brought more snow and cloud. Post holing upwards we made the summit about midday. It was the second ascent of the peak and my first time over 7000m, we were both knackered. There wasn’t any view due to the clouds so after a quick selfie I was keen to get off down.

I was pretty sure our best option was to descend the east ridge until it terminated in a huge cliff at which point we would abseil down the north side on abolokov’s before regaining the ridge again at a col. From here it looked like an easy walk down to the valley and basecamp. In the end, dense fog turned the relatively easy but quite complicated east ridge into a real navigational challenge. I loved it! However, after falling into three bergschrunds I decided to call it quits for the day. The tent fitted quite nicely into the last hole I had made.

By now there was little food left, it dumped snow all night and we didn’t actually know where we were due to the dense cloud, so it wasn’t the best night ever. Dawn brought poor visibility so we stayed put for a few hours until it improved, which it did and we pushed on. At this stage avalanches were our main concern but there wasn’t actually anything we could do about it, as we had to get down. There was no Plan B at this stage.

Fortunately, the cloud cleared and allowed us to identify our location exactly allowing us to descend to the col without incident. From here we had planned to descend to the north towards our basecamp. However, from the col it was clear that the southern slope was easier and safer even if it did descend into an unknown valley, we had no map. It was a no brainer really and got us safely down to the moraine without incident.

The following day we followed the valley down over what turned out to be a purgatory of loose boulders and soft muddy moraine. Not the most fun I have had and a day I don’t care to repeat. Amazingly the valley opened out onto grassy

slopped just above the small hamlet where out Liaison officer was living with the village headman, perfect. Big celebration followed with many rounds of rancid salted yak butter teas. It turns the stomach but you get used to it!

The last remaining issue was that basecamp still remained in another valley and needed to be retrieved. Nick refused to get out of bed the following day but I managed to recruit some local yak herders with motorcycles to drive me round to our valley and help me carry out the gear. Due to the use of bikes I was back by lunchtime to find Nick running the local crèche teaching English numbers to a large group of children, how the mighty have fallen!

Accounts (£) Income

Mount Everest Foundation 3250

Montane Alpine Club Climbing Fund 1500

British Mountaineering Council 1050

Total 5800

Spending

Visas 360

Flights 2088 + 750

Insurance (AAC)

CTMA Peak Fee and in country travel arrangements etc. 6825

Hill food 320

Mountain gas 60

Base camp food and equipment 150

Miscellaneous expenses in Tibet 350

Total 10,903