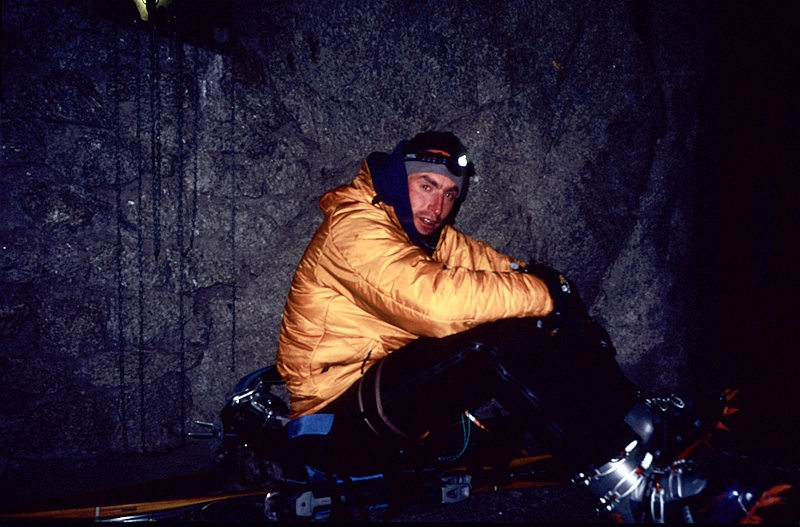

Myself on the first bivouac of a winter attempt of the Colton/MacIntyre on the north face of the Grandes Jorasses around January 1998. This seven day, quick hit from Britain came about when Jules Cartwright heard that a few mates had climbed this route, so we hot-footed in my van, day one, and jumped on even though the weather was looking a little shaky and the conditions on the face were far from good. Hit by a storm on day three of the trip, we had a second bivouac where we both hung all night waiting to be plucked from the face. Day four entailed a memorable descent and a flounder to the hut. Day five was back to the valley and beer and day six was a drive back to Britain. Day seven I think was a rest and day eight was back to work as a PE Instructor in Gartree Prison. No summit but this still remains as one of the most undiluted and memorable experiences I have ever experienced in the mountains. Today would we have been called reckless and idiots and castigated by the internet posse?

At times, things appear to naturally occur in clusters. I’m sure this phenomenon has also been noticed by some think-tank people, who no-doubt will be paid vast amounts of money to give this theory a title but I have not heard of one so I have called it the Cluster Theory. I’m also sure that many people will not notice these natural occurring coincidences and will continue oblivious with absolutely no effect on their lives at all. I am not one of these people. I notice these clusters and over the last three or four days I have noticed a cluster that has had an effect.

Five days ago, via email, I had a conversation with a friend, who for use in this post I will call Jon.

Jon lives in Chamonix, he is a very active mountaineer and on occasion, when I am living in Britain, I will send him an email to ask his opinion about the conditions in the mountains around Chamonix. Sometimes, when I contact Jon to ask about conditions it saddens me; it feels like I’m losing something, even letting myself down.

Several years ago I did not have friends who live in Chamonix and the internet was something of the future. There were of course, the Alpine bongo drums and the French whispers, which were often incorrect, making the adventures large and memorable.

The feeling of excitement and anticipation on the drive, or sometimes the flight to the Alps, regularly threatened to explode from my friends and me, something similar to the avalanches that we often experienced rumbling down the cliffs all around us, after we had become involved with an out of condition climb, combined with a shaky forecast. Even now, especially when I am living in Chamonix for the winter and sometimes when I’m not, I will just go and try a line without anyone having climbed it that year, the year before or maybe for several years. I will go on gut instinct, not concrete evidence from the internet or by badgering friends. I will take a chance with what I get and use my judgement and experience to make an educated guess or accept that an adventure, or maybe even an epic is about to unfold. This, I’ll readily admit, may be the realm of the more fortunate – I have lived five winters in the Alps and I have made choices in my life that give me this opportunity and the time available. I understand this is not possible for everyone but I have long had the opinion that in today’s society of instant information, a large proportion of climbers are becoming followers and it appears, this need for a nearly certain outcome is becoming the norm.

In my opinion this cry for as much information about conditions on certain climbs leads to a less satisfying experience. Going into the unknown, opens the mind and electrifies the senses and the absolute joy when taking a chance turns to success, gives a feeling of euphoria. This, stepping into the near unknown for me and some of my friends, has been one of the main reasons to climb in the mountains and to be a mountaineer over the years.

Speaking to Jon, who had just returned from two attempts at a difficult and seldom climbed route on the North Face of the Grandes Jorasses, he was in total agreement that not every climb has to have a furrow made by a multitude of avid internet scanners or be in stonking condition before attempting to climb it. In fact, Jon said, attempting the climb at the moment, in difficult, ‘out of condition’, condition, was the challenge, this is what he was looking for and because of the difficulties involved, the climb became more memorable and rewarding.

I returned an email whole heartedly agreeing and continued by saying, that although a cliché, it is the journey that is the most important and nowadays there appear to be too many people who want a trophy or the kudos or the Facebook status and Jon’s ‘failing’ has actually given him connection with the mountain and long lasting memories, more so than he would have had if he had just romped to the summit climbing perfect névé, while following in footsteps of those who have gone before with a queue chomped at his crampon heels.

Three days ago – sitting in Wetherspoons, I watched the rain hit the herringbone flags in the centre of Fort William and people run down the street wrapped tightly inside their rain jackets. I read a report in the Guardian by Philip Hoare with the headline; Ladders on Everest are just the latest step in our commodification of nature. In this report Stephen Venables was quoted:

“The mountain has become a commodity, to be bought and sold like any other, we humans have come to expect the natural world to come commodified, negotiated, shaped to our needs. From high to low, there’s nowhere we can’t go, nothing we can’t do. In this age of the Anthropocene – the era of human manipulation heralded by the industrial revolution – it is a given that we have tuned the environment to suit ourselves. Dominion is all; human ingenuity has encompassed the planet. Now pass me the phone: “I’m on the mountain.”

Hoare went on to write, “What mystery is left when the roof of the world resembles your loft conversion?” Well Philip, there is actually no mystery left whatsoever in climbing the South Col Route on Everest and anyone who is a climber knows this but ‘the followers and trophy collectors are of course not concerned by this.

What I am concerned about, is the increase in the lack of mystique in climbing as a whole. This concerns me I suppose because I feel people are losing out on the true essence of climbing. I know this is my problem and I also know there are many people out there that will say having an adventure and deep rooted memory, is irrelevant to them and standing on the summit is the be all but it is this uncertainty within climbing that distinguishes it from sport and makes it very special. It is this stepping into the unknown, the un-measured experience in a time when so much is controlled and regulated – I would say this is the truly rewarding and deeply soul satisfying experience that a large percentage of the climbing community appear to be moving away from. The more this guaranteed success is embraced the more the experience is diluted and the more climbing becomes sanitised and regulated by people who have never had this experience and the more climbing for adventure will suffer.

In twenty years’ time, will climbers be arrested for not wearing a helmet or not having a valid rescue insurance policy? And will these laws come to pass because the people making our decisions for us do not understand that climbing really can be stepping into the unknown, it can mean having the freedom to attempt to climb something not in the best of condition or at least, the best of condition for the masses? Even now, people are forced to stand internet trial and defend themselves when the internet posse bay for blood if a climber has been so stupid to make a mistake or attempt a climb that has not been in pristine condition. Certainly on occasion, people have made a bad call or been plain stupid, but we don’t all need to have, or in many cases, want to have, perfect, forgettable, following the crowd conditions and a plethora of information. The conditioned climbers out there should remember this and accept we are not all after the same thing. There are still people who want to challenge themselves and have an adventure.

I utched my high chair closer to the table and sipped espresso and went on to read a second Guardian report, this one was written by Jason Burke with the headline, Everest may have ladder installed to ease congestion on Hillary Step, but unlike the first report, which was telling me nothing surprising, this report was shocking and it was shocking because of the comment, which I’ll admit may have been reported out of context, by Frits Vrijlandt, the president of the International Mountaineering and Climbing Federation (UIAA), who said the ladder (on the Hillary Step) could be a solution to the increasing numbers of climbers on the mountain. I would say take down all of the fixed rope and the ladders, stop using oxygen, a performance enhancing drug and let people who want to climb Everest, actually climb Everest and then, a solution for the traffic jams on the Hillary Step would certainly be found. An even more shocking comment from Vrijlandt followed, “It’s for the way down, [the ladder] so it won’t change the climb,” This must have been taken out of context as I do not believe anyone who knows the slightest about climbing, seriously believes placing a ladder on a mountain will not change the nature of a climb?

This Cluster Theory bouncing in my espresso infused brain then began to flash like a meteorite shower and extend to an episode from earlier in the winter here in Scotland. I was accused of FOMO (fear of missing out) by someone who does not know me. This spurious accusation, (as if J) came from a friend of a friend on his Facebook status after I had cried in dismay when he posted a picture of a crag and a few words about attempting a seldom in condition and even more seldom attempted climb. The climb was one I was very excited to try myself and I knew it looked in reasonable condition because Katy, my girlfriend and I, had taken the two-and-a-half hours to walk into and two hours to walk out of the crag in quite harsh weather. Katy and I climbed Umbrella Falls that day and very good it was too but a part of the day was to check-out other possibilities for later in the week.

I did not begrudge my friend an attempt to climb the route – which actually, I think he was only attempting after he saw a picture Katy posted on Facebook of the crag, which, after I moaned so much, she took it down to shut me up – not at all, he had every right to be there and try the route. I would have been pleased for both him, and his partner, had they successfully climbed it and proudly told the story but they didn’t. In my mind, opening up this climb without a story to tell, to people who had not used their imagination, judgement, leg power and suffered the discomfort to check out possibilities for themselves, devalued the experience and lessened the adventure for those who had and wanted a wild, un-hooked and challenging time – possibly something similar to that of the first ascent. On a personal note, I also hate the stress of racing people and competing to be the first to reach a route and so would rather not bother if it comes to doing that but maybe that is my problem.

I am aware for some people this makes me sound selfish and they will not understand my feelings, and that’s fine, we can’t all be the same. I don’t think I am selfish and I don’t think holding on to some information about an in-condition climb is selfish either. When did it become law to report to the masses about conditions? I would argue that once a climb has lost its mystique, it loses a massive part of its character, well, at least it does for climbers who find the adventure side of climbing very important and sometimes it may be worthwhile holding back or at least holding on to some of the finer details and pictures to spare others who, like me, want an un-diluted and un-crowded experience which is becoming more difficult to receive in today’s instant access society. So FOMO, no … more FODE, fear of diluted experience.

I also know there will be people reading this who say, ‘don’t look at the internet’ and I would answer by saying in a lot of cases I don’t. I rarely read conditions reports, as most of the time, I would rather go and check for myself and not be swayed by the judgement of others. I do not scour the internet for up to date pictures of crags or read blogs that heavily feature condition reports. But why should I not be free to chat with friends via Facebook and see what friends are up to? Why should I be penalised from highlighting stories I’ve read in the press that I want to share? Why should I have interesting writing kept from me and why should I not be able to advertise a piece of my own writing I wish others to read? The internet is here to stay and it is part of modern society and I love it, it is such a great resource, but for climbing, and especially reports and pictures of climbs and conditions, I think it is changing the essence of what climbing is about.

What is climbing becoming? Well, more adventurous and imaginative, it certainly is not!

The Cluster Theory continues…

Yesterday – Waking at 5am, the stars flickered in a clear sky and for the first time in this winter, I had to clear the windscreen of ice. Guy Robertson and I went to climb on Carn Dearg and, as for the whole of this strange winter, judging the conditions and the weather and deciding where to climb was nearly the crux of the day.

I had been staying in the CC hut, Riasg, at Roy Bridge and knowing how severe the snow storm had been on Saturday – when Tim Neill and I had failed to leave the Aonach Mor car park – my gut was saying, ‘try Cairn Dearg’. It also helped that a few guys from the hut had been to Ben Nevis the day before and had taken a couple of photos of the crag, which at that time, looked wintery but not at all a certainty. The fact that these guys, experienced climbers had bailed, due to the amount of snow, also did not bode well, but as stated above, at times you have to go on instinct and experience and have a punt.

Also, over the last few days, I had been on Facebook and in my newsfeed as normal; I could not fail to miss the odd picture and conditions headline for Ben Nevis. I did not read any of these reports but it was obvious the amount of snow on the hill was a debilitating factor that was stopping people in their tracks.

6.30am – Daylight, and like my frozen van windscreen, for the first time this winter, walking to the CIC Hut with the alpen glow warming the white summits made up for much of the battling. We were still heading for Carn Dearg, but with open minds and a monster rack of gear which would hopefully cover all bases.

9.00am – Gently, I flicked an axe. The pick curved in the cold air and penetrated a thin skin of ice. Gentle, the second axe-pick connected but with downward dragging force, the pick puckered and wrinkled the frozen water until it caught and held on some hidden obstruction. I breathed deep and stepped from the snow. Above me, the steep corner with a continuous stream of thin ice beckoned. And above this, the two hundred and eighty five metres of Fowler and Saunder’s, thirty five year old climb, The Shield Direct. Flakes, chimneys, rock-overhangs, snow-fields, overhanging-ice, history, reputation, connection, surprise. What was going to happen, well of course I didn’t know because I had not even read the route description, we didn’t even have a guidebook and we were here on a gut instinct, not an internet report?

OK, enough said, I’m off now to tweet and Facebook this blog post and drink more coffee and wait for the next cluster!

Nick Bullock on the first pitch of The Shield Direct. Did they successfully complete the climb or did they bail? Was the ice continuous or did it peter-out? Did the snow and wind stop the ascent or not? Did the attempt of this climb come from following reports on the internet… No. Was this climb a step into the unknown and because of this a much higher quality experience… Yes.