[I took this picture of a starling yesterday, it reminded me of a chapter from Tides. Below is a long and less edited version of what became chapter 34]

Please Queue Here

I sit on a stone wall and soak the afternoon sun. The newly constructed entrance of the Midi Téléphérique Station is in front – glass, metal, stone, wood – the structure proudly shines. How many times in my life had I sat and waited like this? How many nervous and excited minutes and hours, even days? But like a sharp stone rubbed smooth by the sea, I could not help think, some of the innocent mountain magic has been lost now with the passing of almost twenty two years.

I had driven from Llanberis to Chamonix at the beginning of December and on the way, I visited my parents who still live on their canal boat called Jasper moored near Northampton. As I stood to leave, my Mum handed me a Waitrose shopping bag of Christmas gifts – mint chocolates, dried dates, a Christmas cake she knew I liked to eat on bivouacs, a really good bottle of South African Shiraz and a birthday card containing cash she could not afford to give. Dad sat in his chair smoking and drinking tea. I took the hessian bag – a bag for life – from Mum’s painfully thin and arthritic hand and after a gentle hug, left the boat. I didn’t realise this was the last time I would see my Mum.

Jack Geldard, my climbing partner for our attempt on a climb called Stupenda, had still not returned from the boulangerie and as I sit and wait – wait with the Chamonix hubbub happening behind – I watch two workers dressed in blue boiler-suits, chipping and spreading salt on a patch of ice that looked like the outline of an island. Pocked brown and jagged – water ran from the disintegrating edge of the island. The slow brown flow trickled and meandered and finally disappeared into a deep crack between paving slabs. Above, starlings look down while standing on the sparkling steel frame of the Midi station.

*

Heavy breathing and the rumble of rocks loosened by the late afternoon sun is the only sound now. Jack and I had skied the Valley Blanche – past The Tacul with all of the routes on the east face I had climbed in 2007 and past The Super Couloir where Rich, Boy Wonder, Lucas and I had climbed in 2004 and on through the Séracs du Géant, to eventually turn right and on to the Leschaux Glacier. On my left, a single ski-tip, old, and very slowly pushed downhill, pointed like a finger from the glacier. I check to see if it is an Atomic, one of the set I lost when airlifted with a broken ankle from the Petites Jorasses. It wasn’t, and with a dull ache in my right ankle, I continued toward the Leschaux hut.

I had stayed in the Leschaux many times and with many different partners including Tim Neill, my friend now for seventeen years after we had snow holed together on out winter mountain leader assessment. Earlier in the winter I had climbed a route with Tim called Fantasia per a Ghiacciatore…

Tim was up front, on occasion I saw his headtorch shine in my direction. We had left the Torino Refugio at six thirty heading into Cirque Maudit with the intention to climb Fantasia, an enclosed ice line I had climbed in 2007 with Steve Ashworth. My lungs crackled and I wondered if this was the same strain of infection that had killed Mum? In my mind’s eye, I saw her lying on a trolley in a hospital corridor tended by ambulance men. Lesley, my sister had been with her, she said they were in the corridor for three hours before being taken to the intensive care unit. My skis cut the snow and my breathing burnt and in the dark, all around, I could see my Mum lying on a trolley in a corridor.

It was light now and in the distilled red striped horizon were jagged mountains. Choughs circled, their wings spread wide to catch the breeze. The Choughs reminded me of the birds from my childhood. As teenager, to feed the ferrets, I would shoot starlings with an air rifle. As a fourteen year old, Starlings were scrawny scavengers, they had nothing to offer, no beautiful song, no beautiful plumage, no grace – Starlings were ferret food. Tim and I geared up, the same as I had geared up a million times, the same as I had geared up beneath this climb a few years earlier when Mum was still alive.

Mum was tall and slim with dark Mediterranean features, but in that frame was strength and determination and as I sat on my rucksack, fitting crampons to my orange ski boots, I could see the deep scar in Mum’s leg where as a child, I had opened all of the draws of a steel filing cabinet, and as the cabinet toppled forward, she jumped in-front taking the force of the and supporting it as it pinned her to the floor with me underneath her fragile body. Someone eventually found us and lifted the cabinet away. SNAP, the crampon locked to my orange boot and the holes in the snow at my feet filled with powder. Arriving home from school once I found Mum covered in oil under her blue Hillman Minx changing the starter-motor, it was a time when cars with diesel engines were rare and this engine had been taken from a large van, it was old and the starter motor was big and heavy, “Pass me that spanner love, I’ll get some tea on in a bit …”

Tim set-off, wading deep snow and crossing the bergschrund beneath the stream of ice clinging to corners and flowing over rock overhangs until it hit the col beneath the summit of Mont Maudit. I followed, clipping to a belay by the side of the first steepening.

There were many times I thought I would not outlive Mum, I thought she would be in that unenviable situation which, I’m sure, most parents dread, of outliving one of their children. I was wrong and as Tim and I climbed higher and the wind on the col increased, this time, for the first time, the situation felt different, I realised if I died, there of course would be upset and sadness from friends and family, but the one person who would have been truly devastated was now gone.

Mum always took a delight and interest in whatever activities my sister and I were involved, to the point that when I became interested in mountaineering and climbing, within months she could name mountains, mountaineers, Scottish winter climbs, summer rock climbs, Alpine climbs, Himalayan climbs, South American climbs – the lot, and she could enter into conversation about the subject with confidence. This of course was not always the best, because pulling the wool over her eyes was now impossible.

Leaving the sun, climbing into the shadow, into the confined icy corner – images and memories flow with every drag of the pick, every kick and swing and pull… I could see Mum totally worn-out, falling asleep in a high backed chair, with a half filled mug of strong instant coffee balanced by her side. Sometimes, so tiered, the mug fell from her hand. Strong coffee was certainly a big part of Mum’s life and she was seldom without one and it was generally partnered with a super long cigarette. It says something about her determination, that after nearly fifty years of smoking, one day she decided to give up…

… up … up, up above, the spindrift rips into the blue sky and swirls… like steam from a mug, like Starling murmuration, like smoke, like ashes… And either side of this slender ice formation, the granite mullions hem us, hem us the same as the strong skeletal Oak that stood either side of the wooden church gates as we wait, just a few days earlier for the hearse carrying my Mum.

Jack and I left the Leschaux Hut at 5am. We had crossed the glacier and climbed the approach slope beneath Stupenda, an overhanging and direct crack line in the Aiguille du Tacul. I was now deep inside a chimney at the beginning the third pitch and struggled to remove the gloves stuffed down my front, but the food in my chest pockets, and the bundles of blue 4mm tat, still bulged like a beer drinkers paunch. The Styrofoam Jack and I had read about in the Philippe Batoux book, The Finest Climbs in the Mont Blanc Range was nowhere to be found, instead, stuck to the dark, beneath the numerous overhangs, was meringue.

Stupenda is given a grade, V A2 M5+ WI6, I’m not sure what this means, grades in the mountains can often be superfluous. I climbed higher, squeezing deeper, deeper into overhanging granite, deeper into the mountain, to finally reach the pitch three belay. Jack seconded the pitch and I set off on pitch four. I swing through the overhangs directly above the belay. Certain I had just free climbed the crux I shouted to Jack, “Hashtag, first free ascent!” But as I pull through another overhang and into another crack and look up, I see flared and overhanging off-width. My hashtag hubris smacks me and I made a pact with myself to try to be more humble in the future.

On the smooth wall to the right are two, spaced bolts. I realise this must be the A2 section and the bolts had been placed for upward progression. I squirm and arm-bar and leg-bar and body-bar until I feel drunk and I can hardly bar no more. My stomach feels punched.

A few summers ago, one wet weekend in the Llanberis Pass, I was climbing with Dan McManus and we tackled a bunch of off-width test pieces in preparation for Dan’s trip to Yosemite. A body eating, E4 crack called Fear of Infection had me nearly vomiting. I slithered and swore and squirmed. Pushing up, pushing down, hanging in, hanging out… thighs, elbows, back, soles of feet, face… anything to stop me slithering and slipping and losing the millimetres that had taken so much effort. The damp rock rubbed raw the soft, sweating skin of my face and I eyeballed the individual grains of wet Rhyolite. Dan, belaying directly above, laughed, he laughed nearly as hard as I had when he first approached me.

“If ever you need a climbing partner, I’m keen; I lead E3 and will follow anything.” I’m sure he must laugh about our first meeting – or maybe he doesn’t, maybe he is comfortable in his flesh and maybe I have learnt my valuable lesson.

The walls either side of this Stupenda were Fear of Infection, but this time I was wearing crampons, using axes, wearing several layers of clothing and the rain was substituted with spindrift, but the nausea was much the same.

My torso was above the highest bolt. I attempted to swing a pick into a clear slither of ice glued to the back of the crack, but each time, only a single tooth caught. I could not swing the axe because of the restricting crack and my body was balanced precariously – taught, extended, I needed to escape these constricting granite chains, but my left foot, shin, knee, thigh, failed to purchase and repeatedly I slithered back to the one foothold inside the crack. ‘You can do this.’ Suddenly I realised how important free climbing this stupid Stupenda had become and my younger determination was shocking.

I wanted to free climb Stupenda for the physical and technical challenge and because free climbing is more natural for me and my attitude – pulling on gear has never felt satisfying. But deep inside, as I climbed higher and higher, somewhere in the back of my brain, was a rusty nail driven deep into twisted grain. I wanted to prove a point to Philippe Batoux, the first ascentionists, because in the past he had openly questioned some of my climbing. There was also the thought of being able to instantly show and tell, show and swell, puff up my chest like a starling. A free ascent of this climb would do it, I would show all the others what a good time I was having in the Alps. But, but, don’t I look down on climbers for lack of modesty, being full of hubris and pushing their ‘great’ ascents repeatedly and forcefully down my throat? In Fact, I was so sick of the spray this winter I needed Milk of Magnesia. But deep, deeply driven was that nail and that nail wanted to be liked and accepted and loved as much as everyone, but that nail was corroded and it filled my brain with flakes of rust…

Knee bar, arm bar, squirming, battling… ‘first free ascent’… millimetres … arm bar …’look at me’… I take hold of the axe jabbed to the drool of ice. Thrutching. Sweating. A millimetre, a centimetre. ‘Still clean.’… Hunting. Hanging. Wedged. ‘Still clean.’ Held in-place by a twisted thigh, body tension. ‘Still clean.’

Level with my right foot was the higher of the two bolts which had a carabineer clipped. I stared; it was tempting for a front point, ‘who would know?’ But I couldn’t, I just couldn’t, because of course, I would know and some of the less honest or should I say, some of the things I have said or done, that I am less proud, still haunt me and I have learnt that my life is more healthy without echoes or ghosts.

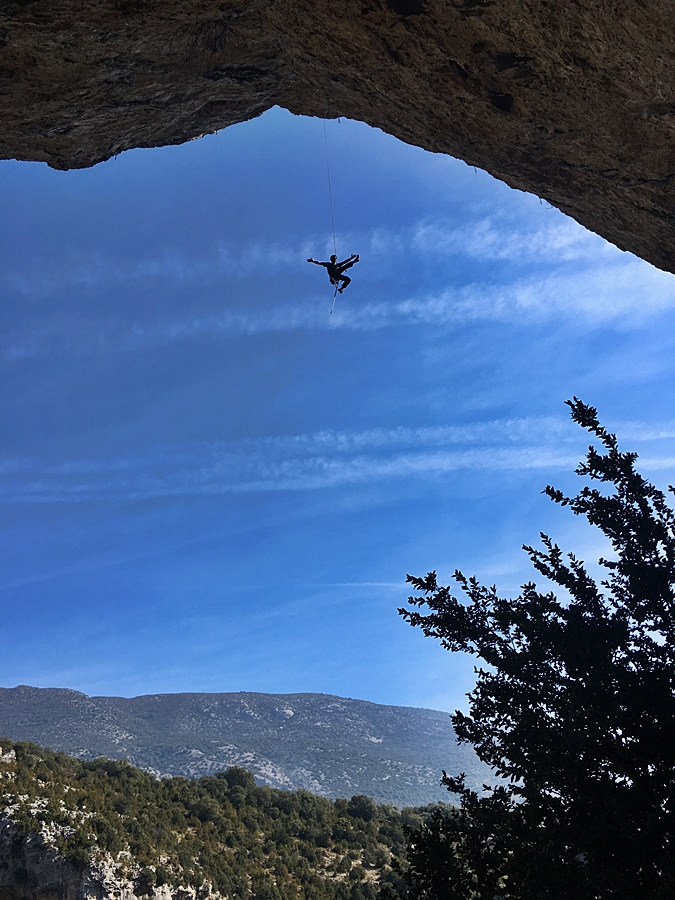

I stripped myself to skin and bone and sinew to make myself light. Ego, and the fear of failure, could, at one time, weigh me down but fortunately, not that often anymore. So what if I fall and the free ascent was lost, so what if I didn’t clamour to update my status – this fight is my fight and my fight alone. I match the axe with both hands – pull and squirm. Millimetres. Millimetres. The right leg flaps and scrapes. Millimetres. Squirming… but the ice grows tired and the axe rips and ice shards explode, hitting me in the face, and I fall like a Starling shot with a lump of lead, fired from a teenagers air-rifle. And as I fall, being scared hardly enters my mind, but for a second, just one plummeting second, being disappointed and even being angry does. But the disappointment and anger was only for a second, and by the time twenty-five feet had past, I was happy and in some way content.

“Are you OK?”

“Yep, I’m good ta.”

Learning to live this life and move through this life is often about accepting the contradiction within us…

I pull myself up the rope and this time, using a front point neatly placed into the karabiner clipped to the high bolt, I managed to find a hook and once more, begin to squirm and thrash and eventually reach the belay.

Three bold and technically demanding pitches follow but finally, finally, I’m stood in the brèche at the top of the climb. Exhausted. Enshrouded by dark. I had taken a claw hammer to my brain, my life is taking a claw hammer to my brain. Mum would have been proud…

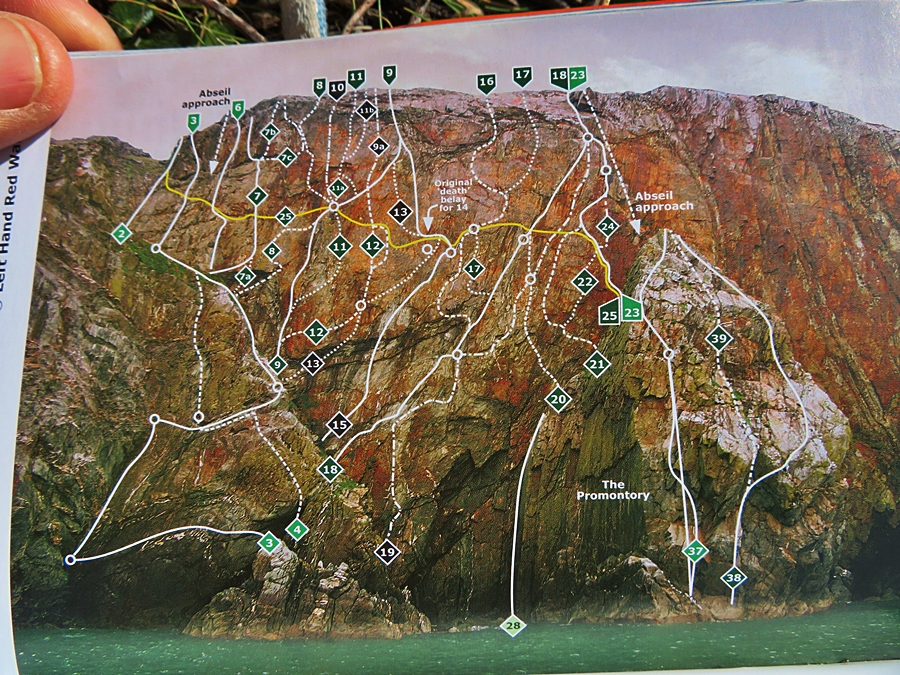

A few days after climbing Stupenda, Jack and I were in the hills again, hoping this time to climb the Dru Couloir Direct, but unlike Stupenda, we knew this climb had been in condition, it had received four ascents earlier this winter. The Dru Couloir held a special place for me, it was one of my earlier, successful Alpine climbs, but it had not been a giveaway and the thought of returning fifteen years later, intrigued.

It was September 2000 when I had driven from Leicestershire to Chamonix with Paul Schweizer. Paul was a reasonably affable West Coast American with a penchant to rant – we immediately connected. Old – older than me anyway – a tad crusty, goatee sporting, round wire frame glasses, straggly hair sprouting from a thinning – quirky, off-the-wall, intelligent, articulate – Paul was an Edinburgh University Lecturer in computer logic, and fifteen years down the line, I still don’t know what this is. To be honest, I think I’m incorrect by calling it computer logic, but this is my limited capacity for understanding the subject Paul actually lectures.

Heavily laden, stepping from the Grands Montets Telecabine, Paul, lumbered, a bowed six-foot something dressed in black with purple Scarpa Vega boots. His weight caused the snow-dusted wooden floorboards to sag. It was 4pm and outside, the wind and snow and cloud were swirling. This was the last lift of the summer; the téléphérique was now closed for maintenance before the winter season started in December. We added several layers and waited, planning to sleep in the toilet and approach the Dru North Face in the morning. A friendly guy from the café guessed our plan and handed us left-over food including cake; he then departed on the final lift of the season. The cake, eaten in the dissolving warmth of the long drop, lost a little of its French eloquence, but was still tasty.

Leaving the cloistering stench of the toilet early, I don’t remember exactly at what time or anything about the approach or even anything about climbing the initial snowed up granite slabs, but I can still smell those toilets. Being American, I pointed Paul at the Nominee Crack… A1, no problem for a 70’s Yosemite Valley dwelling Septic, but Paul forgot to say, at that time in the valley, he was one of the new breed of climbers – living, smoking, drinking, partying, living free and climbing free, not with aid – he had as much an idea about aid climbing as I, and that was about as much idea as I had about computer logic.

Six hours passed, possibly longer and in that time I sat and willed and looked around at the sheer walls feeling isolated and exposed. Paul at last made it to the top of the Nominee Crack, a bowed overhanging crack, by fighting and back cleaning, he had left me little to grab and many years before big handled axes and no leashes, I attacked the crack in a free, thrash, grunt style and still wearing my monster rucksack. Needless to say I struggled and in one moment of pulling-like-a-train desperation, an axe ripped and the massive adze of my straight shafted Grivel Super Courmayeur smashed me in the face with a sickening thud and the splatter of and taste of blood. I had ripped my cheek, making me think I’d smashed the bony, inferior orbit just below my eye and blinded myself. But I could see stars, so maybe not.

Flopping onto a small sloping ledge alongside Paul, I was bleeding and bruised and exhausted. We stayed on the ledge and in the night it began to snow and the snowflakes were the biggest and most perfectly formed, they settled and covered our gear. In the morning the snow continued but we decided to climb-on. Following an old description and after most of the morning, Paul, on the sharp-end, and getting very close to the ice in the continuation of the couloir, was squinting and clearing condensation from his round glasses and looking at some desperation lying between him and the easier ground to his right. Blankets of powder fell regularly making the steamed up spectacles even more of a problem. “Fuuuucking hell man, this is shit.” Paul drawled while balancing, cleaning glasses and moaning, before being hit by another cloud and having to repeat the whole operation again. Eventually with avalanches pouring down around us, we bailed.

A few abseils from our high point, in the slabby open arena and on full rope stretch, I kicked into the snow making a small step and to save time, unclipped from the rope to allow Paul to come down while I set up an anchor. The ropes pulled through my belay plate, springing out of reach. Paul began abseiling and suddenly yelled, and for once it was not a laid back American Hippy drawl, his voice sounded sharp and intent, near manic. “WATCHOUT MAN, AVALANCHE.” Looking up, I had time to see an arc of white pouring from the top of the most beautiful and direct cut, cleaved into the mountain – a steep and overhanging darkness, a siren with a smattering of ice baubles and granite flakes like the fins of sharks – mesmerising – this was the mythical Dru Couloir Direct, first climbed by Tobin Sorenson and Rick Accomazzo in 1977, but coming from the tooth filled mouth was a wave of whispering white and as the snow hit, I reached up grabbing the dangling ends of the ropes which fortunately were now in reach with the weight of Paul. I twisted them around my wrist as the snow hit. My shoulder stretched as the snow built and poured over me. Hanging, tucking my chin to my chest, I managed to gulp air and after about two days, the snow slowed and turned to a trickle.

Reaching the Dru Rognon beneath the West Face, Paul and I stripped off layers in the warm sun. What had just happened? We had escaped another world – a dark and foreboding world where dragons live. This we had now, this was another life, a warmer, safer life. We began the walk downhill but soon collapsed and made a bivi in the damp, pine-needle earth, below trees with flitting birds that pecked cones and hunted insects. The next day we thrashed the giant rhubarb and down-climbed disintegrating rubble because we didn’t know about the ladders on our left that safely led to the Mer de Glace. Sometime, mid-morning, surrounded by sweet smelling people, we caught the Montenvers Train and returned to the green valley.

Armed with a more up-to-date route description, several days later, Paul and I returned to the Dru Couloir. We had a bivi before, a bivi on route, a bivi at the Brèche and a bivi on the Charpoua Glacier when we abseiled too low and missed the turning for the Charpoua Hut. But we had successfully climbed The Dru Couloir and we were happy.

Jack and I had a leisurely approach to The Dru North Face and we had a leisurely bivi on the glacier. We cut depressions in the snow to allow our blow up matts to sit, we chatted, melted snow with our efficient gas stove, drank tea, ate biscuits and at 4.30am, left to climb the Dru Couloir Direct. At approximately 3.30pm, we stood in the Dru Brèche, looking through a granite picture frame at a cumulous enshroud Mont Blanc. A leisurely return to our bivi by abseiling the line was uneventful and after a cold, but safe night, we prepared to boot back to the Grand Montets station.

Leaving the bivi, the same bivi Pete Benson and I had shared when we had climbed the Dru North Face in a bitter winter high pressure, 2008, the memories flood. We passed beneath a new line I had climbed with Jules Cartwright called Borderline, beneath a line I had climbed with Andy Houseman and Ian Parnell called Russian Roulette and we walked in the fifteen year old footsteps of Paul Schweizer and myself. The sun cast jagged shadows as we crossed crevasses and beneath my feet, I imagined the depth and age, the icy layers and history. My boot sank into warm snow and I remembered more recent events and the ski-out after Jack and my ascent of Stupenda.

I lay on a wooden bench looking at the stars. Jack lay on a second bench doing the same. There were millions of them, a Starlings chest of iridescence – black plumes smattered with silver flecks amongst an oil slick of green, blue, purple and red. It was half past midnight, Jack and I had skied the bottom section of the VB and walked the steep snow-slope, leading through the woods to the small wooden hut at the start of the narrow, and zigzagged, James Bond Track. The track would eventually lead us back to Chamonix. I sat up and looked across the orange glow of town, across the moving white headlights, the dogs and cats, the parties, the blue shutters, the frosted pewter cobbles, the cafes, the silver icicles hanging from gutters, the stationary lorries with smoking chimneys and on – my eyes moved on to the snow slopes of the Brèvent and Flégère and the piste bashers out on the hillsides, moving around like a War of the Worlds invasion – flashing yellow lights, powerful white beams, smoothing and grooming, hunting and searching.

“How you feeling?” Jack asked.

“I’m totally knackered,” I replied without taking my eyes from the moving lights of the piste bashers that were now blurred by the cloud of condensation rising from my mouth. “Bloody love this feeling, never want it to end.” And then it hit me, because of course, it will end. I had lost my Mum and I had already crossed the halfway point in my own life and as I lay on the bench looking at the stars, I knew this queue was the same queue as we all stood, and this almost made me weep, but it also made this time expanding, opaque, alpine life and the sacrifice to live it, even more worthwhile and wondrous. And as I lay in the chill, with thick steam rising from my clothing, I realise that I still cling to the alpine innocence, but with growing older, it needed more of a jolt. But with this growing older, other facets also became more important – the shared experience, the connection to the surroundings and of course the memories.

And in the branches of the trees surrounding Jack and myself, I imagine are Starlings, such gregarious and beautiful survivors.