Kenton Cool abseiled into the Rive Gauche looking for a climb called Home Wet Home. He stood beneath a thinly iced cleft that he thought was the climb and rang Jon Griffith and me who were stood on top of the crag. His opinion was delivered in the typical reserved Cool style, “It looks shit mate” As I abseiled I actually thought that the climb looked good. Steep, a tad loose, a sheen of ice, not-a-lot-of-gear and what a brilliant line. Reaching Kenton I voiced my opinion, “It looks good hey?” “You’re bloody mad mate. But have a go by all means.”

A few hours later the 1st ascent of Homeward Bound was successfully climbed. Kenton seconded the 70 metre pitch and by the top had changed his opinion on the quality of the climb but he nodded knowingly, convinced his judgement on my mental state was correct.

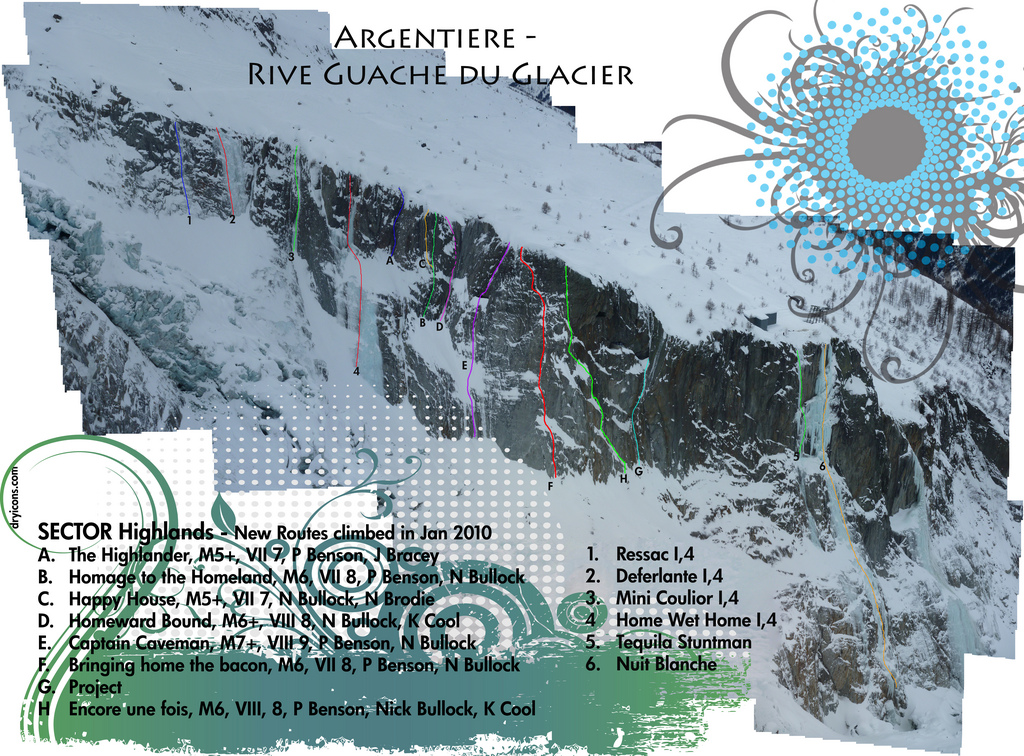

Abseiling into the wrong line opened opportunities. This area of the Rive Gauche, easy angled at the base with streaks of ice, then steep toward the top, glaciated smooth and peppered with tufts of turf and moss in the middle, was a convex, complicated swathe of seldom bothered with. It is surprising that no-one has climbed in this area of the Rive Gauche as it is hemmed by classic climbs such as Nuit Blanche, Tequila Stuntman, Mini Couloir, Home Wet Home and Deferlante. Although it’s probably not that surprising when you consider the whole of the European Alps surrounds you.

A couple of days later Pete Benson and I returned and climbed a line Kenton and I had spotted on the first visit. Homage to the Homeland, a two pitch VII/8 or M6 felt quite sporting at either grade, Pete wanted to grade it Scottish VII/7 as he was afraid it had probably been climbed in 1926 by Lionel Terray. Eventually I convinced him that the climb was technical 8 and I was sure Terray would not have been bothered about climbing in the Rive Gauche. Fired up, Benson went across to opposite side of the glacier and took a high resolution shot of the crag. That evening I sat in front of the log fire and zoomed in on the picture. There were possibilities all over and as the weather was still unsettled, where better to climb.

Four more climbs followed the two we had already climbed giving a total of six new routes. All of the climbs are short; Highlander, Happy House and Homeward Bound are just one pitch. Homeland is two pitches, Captain Caveman and Bringing Home the Bacon are three pitches. All were led ground up, placing gear on lead. A common feature of most of the lines is the lack of footholds. It’s amazing how it messes with your head not knowing whether it will be possible to stand in balance and place gear (if there is any gear!) or whether you are just going to have to keep pulling in the hope of a foothold.

Neil Brodie and I repeated the first pitch of Homeland. Brodie chuntered all the way while leading the pitch, “Benny’s mad, there’s no gear, what was he thinking?” I reminded him that this first pitch was probably Scottish VI/6 and he had been clipping too many bolts. “But I don’t do this sort of thing well Nick.” I then reminded Brodie that actually he did do this sort of thing, and, he did it well. Brodie was one of the boldest winter climbers I knew, and with that he got a grip and started to enjoy himself.

Instead of climbing the top pitch of Homeland I wanted to try at a steep crackline cutting the buttress to the left of the original finish. The crack proved to be sustained and technical with a bit of burl, but well protected. Three star climbing marred only by hollow hanging daggers of rock near the overhanging exit. Bypassing the daggers on the right was a thought provoking experience, (you have been warned) but an experience that made the climb more memorable! The climb is called Happy House after the Suzy and the Banshees song about mental institutions. Neil topped out after seconding the route enthusing, but later by skype he was particularly damming in typical Brodie style “Yes it’s similar to climbing in a Scottish quarry” Since then Neil has been regularly talking of going back to climb in the Scottish quarry!

Pete Benson and I returned to the Rive Gauche unperturbed by Brodie’s comment. The climbing actually was very good. A sabre cut corner/groove/cave/crack was the objective. The line started from the base of the crag, a thin ice streak start into a turfy, no foothold flake, topped by a cave guarding the final thirty metres of offwidth.

Pete and Jon Bracey had gone in to attempt this line a few days earlier but on a previous mission on the right side of the crag, Bracey and I had been stopped dead by a massive cave similar to the one on this line, this had resulted in a 70 metre free hanging prussic. I think Bracey saw the same happening and chose a new, but more certain line to the right of Home Wet Home, (highlander) leaving one of the best and most obvious lines to be attempted.

Captain Caveman took two visits. The first visit was going well. Two pitches completed I stood in a massive cave belaying Benson. He stein pulled out of the cave (can opener, upside down axe pulls), feet smeared level with his head. Stein pull into stein pull, a blob of turf, a bulging corner, crampon points screeched on smooth rock. Stein pull, swap hands, stein pull and finally a foothold. Pete now had grave reservations. The crack above was steep, wide and verglassed. The biggest cam we had was a number 4 and this crack was going to eat number 4, 5 and 6 camelots, and after it had eaten the gear it would then devour (piggy) Benson for lunch. Run away!

Benson and I returned two days later armed with a double set of cams and a 4, 5, and 6 camelot. I abseiled directly into the cave wearing a big duvet jacket and a warm pair of gloves happy that the offwidth looked easy; (A second’s wisdom is great isn’t it?) Pete set off from the cave pulling the overhang with a new found vigour (or was it that with prior knowledge he knew exactly what gear he needed to reach the resting spot and then he could pull up the hundred weight of ammunition to tackle the remaining 20 metres of burl.) Pete fought the crack using a variety of methods and a variety of gear and eventually after an hour and a half slithered around the final bulge.

Seconding the pitch, I was surprised at how technical the climbing was. I had imagined a thrutchy burl but there was nothing at the back of the crack to hook and it was too wide to jam body parts. The only way was to smear feet on dribbles of ice, tiny tufts of grass, razor edges of rock, and layback from an upside down head of the axe torques. The crux moves were pulling the final overhang. The verglassed rock on the right was smeared with blood where Pete had ripped his trousers from pushing his knee against the rock. I slithered and slipped and scraped and swore and slipped and slipped and swung and slipped, but eventually pulled from beneath the overhang, peddling, pumped and wide eyed and full of respect for a great lead. “What took you so long Pete?”

Each visit to the crag I longingly looked to the right at the largest clean swathe of rock and a blunt spur. Benson’s picture had revealed a white line zig-zagging the face and in my mind it had to mean there was something. A ledge, a crack, something that was causing the snow to stay. But until now I had been perturbed by Neil Brodie’s comments, “Nick, you’re f***ing crazy if you just launch up there without at least looking… even better, take a drill.”

Abseiling the spur I got more excited with each metre descended. Apart for the exit groove which was off to my left and out of reach of inspection, the line was a crack system running the length of the crag. Excited I waved Pete down who got stuck in and led the first two pitches. Lightening strike cracks, bulges, turf blobs, and as much gear as you wanted. I led the final pitch, a 40 metre crack line that ran out of crack and gear about 10 metres from the top. An unprotected insecure shuffle beneath a roof had me talking to myself until at last a foothold, a clod of turf and some gear materialised steadying my nerve enough to top-out. Pete seconding enthusing that this climb was one of the best he had climbed anywhere. Quite an accolade I thought given Benson’s credentials. We christened the climb Bringing Home the Bacon, the best climb of the new routes.

Climbing is a great activity. It is different things for different people. There will be many that say these routes are pointless, small and insignificant lines amongst the mountains and not worth bothering with. Well that’s fine, don’t do them. But for my mates and me these climbs were great adventurous days out when the mountains were out of bounds. This type of climbing was a real test of nerve. Pushing on into no-mans-land with no idea what grade it would be, what protection was available and what type of climbing would come is unbelievably rewarding no matter where it is. The climbs will never be great mountain classics and we didn’t climb them to spray about what great climbers we are, but having had some really fantastic days out, we wanted to share the climbs.

Grading has been a problem. All of the climbing was completed in a similar style to that of a Scottish new route but we have given M grades for people used to that system, (all at a moderate M grade, but feeling a tad spicey as you have to place gear and at times run it out).

On all visits we took an extra abseil rope or two which we left in place as we never knew what would happen. This proved to work well as the trees, or the metal bars of the tunnel entrance are quite far back and pulling ropes would have be a problem. The climbs that start from the very bottom, ie, Captain Caveman and Bringing Home the Bacon were reached by abseiling from an abseil rope and then abseiling from the end of this with the climbing ropes. There is always a reasonable way out by climbing the ice beneath Home wet Home and then climbing out on that climb which is a great route, or one of the more easy lines to the left.