I’ve just finished the third draft/edit of what will hopefully become my second book, provisionally called, Tides. wuthering and erosion.

Below is chapter 24. how Soon is Now. This was first published in the on-line magazine Mountain Pro Magazine

How Soon is Now.

The edge had returned to the Welsh hills in February. There was no snow, only frost thistling the yellowy slabs of Rhyolite. Each morning the grass was white and the black slate wore frozen cling-film. I stayed on my own in Tim and Lou Neill’s house next to the chapel in the centre of Nant Peris. The sun filled the sky and melted the frost and cast shadowy crosses on the white walls inside the house. When, after breaking my ankle on Omega, and my first winter season in Chamonix was cut short, I returned to Britain feeling sullen having been torn from the mountains. On that occasion I stayed with my friend Janet, in her house in Quorn, Leicestershire. I counted the hours and days and weeks before I could remove the plaster and return to Europe. I sat inside Janet’s terrace house in stasis, inert, stuck – the waves washed over me and I almost drown. Time, that most valuable commodity, was spilling. And now, my winter had been cut even shorter, but returning to Llanberis felt like coming home, the town had taken place of my home in Burton Overy, it was somewhere I was starting to become very attached. Friends that were still in town and not in Scotland or the Alps welcomed me and I didn’t begrudge being back or even the injury I now had.

Every day I ran with the frozen bog beneath my feet. Sometimes my foot would break the crust leaving a dark footprint with a white outline. The hills directly accessed from the house were my favourite, Elider Fawr, Foel Goch, Y-Garn – sheep shorn mounds, all frozen and crisp. I ran across the worn track at the top of the Devils Kitchen. Open space. A buzzard cried in the blue crackling sky. The Glyder plateau, spikes of rock, like hewn standing stones. On the lee of these monoliths was soft moss, but the rock was as rough as a terrier’s coat on the windward side.

One day I ran and scrambled Tryfans North Ridge. Where it was possible, I jogged, and where it was not, I scrambled. Passing people, they looked aghast when they saw my arm in plaster. I waved and said hello and continued. I climbed direct, the cold friction felt clingy and safe. I remembered climbing the same ground, the same rock and the same features in April, seventeen years before when I trained to be a PE Instructor. I jogged a wide ledge where I could still picture Mark Bentley, my roomy and friend from Bolton, crawling on all fours with the wind snickering at him like a magpie and afterwards brushing away the sleet leaving dark damp patches on his knees. The air around me now was frigid and empty; it caught images and dreams and carried them away over the heather.

Crossing Bwlch Tryfan, I looked once again to my past. I saw a group of trainee PE Instructors trying to remember how a compass worked. My toes crunched on the surface of rock covered with moss and grains. I smiled thinking that some things hadn’t changed. On and on and on – panting, chest heaving, deep heaving breaths, the streak of dried sweat. Scrambling Bristly Ridge, swinging legs and pulling. Empty air with blank open space. My broken wrist ached, but not enough to stop me. Then, once again, I was out of the dark and onto the glaring Glyder tops. The rocks and the hills looked like an over-sharpened photograph and in the shimmering distance, the sea was a dark green sheet. Jet aircraft screamed across the blue leaving white scars for the buzzard to thread. But eventually the scars faded and the buzzard disappeared into the distance.

I ran from the summit of Glyder Fach, dodging and balancing, my feet catching edges, stubbing toes, ‘nnnrrrrgh‘… The pain, like a broken heart, was only temporary, although the pain from a broken heart would remain for longer and hurt more.

I stood on the edge of Cwm Cneifion. Skidding feet turned sideways. Rocks bounced and whirred and hummocks of grass broke revealing the red beneath. I stopped and stared at Clogwyn Du, the little black crag at the top of the Glyders. Raven coughed. I could see ghosts of winters past.

Running the edge of Llyn Idwal, around the well-worn path, the water sucks and filters through rocks rubbed round. I watch Sam Sperry, my ex-girlfriend from Leicestershire with Blue, the brindle Staffordshire Bullterrier pulling on the end of his fully stretched lead. I see Sam’s long blond hair blowing wild in the breeze and her torn jeans with flickering frays and I watch her ‘take me or leave me’ twenty eight year old attitude catch in the breeze and carry across the ancient water.

I jog onto the Ogwen Cottage car park and see a group, including myself, hucked tightly together on tarmac, cooking in the cold, having navigating the Carnedd’s all the way from Drumm to Pen Y Ole Wen on our summer Mountain Leaders Award. I run the roadside by Llyn Ogwen, the water unruffled. Gulls skim the waters clear surface looking down at a version of themselves. Cars speed past. The people inside with heavy right feet and heavy heads, rushing to somewhere from somewhere, going nowhere or anywhere. I can smell fumes and warm worn oily engines. A silver wheel trim lies in the gutter – a plastic starfish washed up and winking.

Whatever happened to Alison Parker?

Alison Parker and I went out for a while when we were both twenty. She had a small upturned nose, short to medium length blond hair, white teeth, taught suntanned skin and a wicked smile, which she wore most of the time. She laughed and she made me laugh and I think for the very short time we were together I loved her very nearly as much as I have loved anyone. She introduced me to Neil Young and Crosby Stills and Nash and Leonard Cohen and The Smiths.

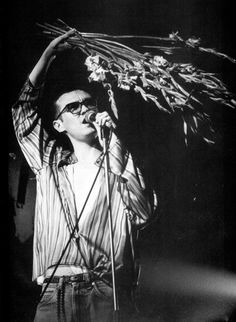

The night before this run I had watched Morrissey on the I-player, he looked similar to how Tom Briggs looked, the time we first met and climbed together in Australia. And later in the evening, I watched a YouTube clip of The Smiths on Top of the Pops from 1984. What Difference Does it Make, the song I ribbed Alison Parker about when we first met and stood next to the cooker in the kitchen. I refused to admit I liked it.

The night before, watching The Smiths from so long ago, plunged me into renaissance – swinging my plastered arm and wishing I had a bunch of flowers.

Where the hell did it all go?

It had been twenty-three years since Alison Parker had bullied and cajoled until at last I admitted to enjoying the music of The Smiths and then we moved close and kissed for the first time while leaning against the cooker.

Morrissey gently shuffled around the stage with his shirt buttons tested to the limit by a paunch. Then, with a bit of a shuffle and the occasional arm swing, he attempted to be dangerous. But he wasn’t, he was just old.

His voice and presence were still electrifying even after all of this time, but how time stops for no-one. Not you, not me. Not Morrissey nor Alison Parker nor Tom Briggs nor Mark Bentley nor Sam Sperry. It stops for none of us.

The music of the Smiths takes me back – back to an attitude of, what difference does it make and panic at the disco – but while I always panicked at the disco I never did think, what difference does it make, or at least, not until now, not until I could run no farther and wring every bit out of this short life.

The Smiths remind me so much of Alison Parker with her vitality and energy and intelligence, she was carefree and dangerous and so much fun.

I wonder where Alison Parker is now and if she has children and if so how many. Does she still have that spark or has life beaten her to grey?

I ran the last few metres until I stood at the side of my green Berlingo, parked at the side of the road near Little Tryfan.

Watching Morrissey the night before made me think that for just the short time you are there – there in your prime, a handsome devil with hollow cheeks and bendy limbs and strong muscle – just for a short time, you may not care about the world, or at least the world outside your world, and you think there is a light that never goes out.

But there is a light and one day it will go out…

Great stuff, man. Seriously. Somehow you have evaded the unidimensional-climber-trope and it’s inspiring as hell. Sure, you blast up some pretty wicked spots on this earth, but when I see (pro)climbers who have more it pushes me harder. Thanks.